“…if they start dressing and acting like soldiers, maybe they’ll start feeling like soldiers, and by god maybe they’ll even become soldiers…”

Note: If you don’t like long winded thought pieces on mindset and SCA Culture, here is your quick and easy takeaway: Get an awesome hat, wear it and learn to take it off and be courteous with it.

For the rest of you choosing to stay, I’m going to attempt to talk about broad concepts on how to improve your game. There are no special moves, I won’t tell you which fencing master beats which and I won’t give you any secret mantras or rituals. What I will give you is a few basic habits and ideas to follow that will allow you to emulate the great fencers until you become one.

Step 1: Emulate the training habits of the successful

Among my friends and peers (small p), within the rapier community there are notable flavours of individuals and a variety of individual motivations for pursuing rapier. Some people choose to start their path in learning rapier because they have a background with Olympic fencing, others because they find it an easier and/or cheaper entry point than heavy. Others because they worry about injury or pain that comes from armoured combat. Some just enjoy using steel swords and the subtle musketeer theme the Society puts out among the fencing community. For myself, I came into the SCA interested in heavy, but ended up learning rapier due to the ease of access and the strong local support.

But whatever the motivation for pursuing rapier, there are a variety of different philosophies behind the approach. Do you just want to get together with friends once a week, have a few fights and have some fun? Do you want to want to win tournaments and collect tassels? Do you want to specialize in a specific fencing master and be able to fight in a reliably historical manner? These are all valid answers, and all these people (and more) exist in the society. But for the sake of this writing, let’s assume you want to improve your game more than just the average occasional pickup fighter. Maybe you want to win a tournament, or at least provide a challenge to some of the strong contenders. Perhaps you want to achieve a level of competency in a grading system (see Lochac Royal Guild of Defence for examples). Then I submit to you that the best way to improve is to look at the training habits of successful fighters.

1 – Picking up a sword and training once a week will maintain skill, not improve it.

If you want to get better, you need to do more than train once a week. You don’t need large formal lessons, pickups or even a sparring partner. At the most basic level, if you can find a section of wall in your backyard you can hit with your thrust and practice distance and stepping drills against at least once a week in addition to your regular weekly training – you will notice improvement. If you can get a pendulum pell or similar to practice moving, thrusting and cutting all the better. If you can get out there 15 minutes every day you’re not fighting, then I guarantee you improvement.

Likewise, if you put a sword down for a period of time, your skills will begin to decline. Now, the amount they decline will be relative to your existing skill level. If you are brand new, been practicing a month and then take a month off? You will lose significant progress, because there wasn’t much to begin with. If you’ve been fighting and training for a dozen years and you take a month off? You may need a week or two to get back to your usual sharpness, but you’ll still be there.

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” – Will Durant

2 – Fight well, or not at all

This rule will likewise extrapolate to all our fighting. The more fighting we do, the better we should become, right? Yes and no.

The more fighting we do where we fight well, using good technique and evaluating our actions will lead to a higher skill. Likewise, if we spend all our time messing about with poor technique and sloppy footwork, we will be doing nothing but ingraining those actions within ourselves. It’s important to have fun and to try new things and a key part of learning is making mistakes and failing. But there is a difference between learning and getting wound up with friends on “Me have sword. Sword fun hit”. I’ve heard comments about this to the tune of “I only muck about because it’s training”, to which I ask people to sit down and calculate the number of hours they spend training vs the number of hours in tournament in an average month or year. How you train in training is how you fight – don’t teach yourself to be a fool.

A final point to note is that stressing an injury only delays healing and can potentially injure you further. Don’t fight injured or sick, you’ll risk more harm than progress.

3 – Take notes, because your memory sucks

Over your fencing career you will be given advice. Some of this will be good, some of this will be bad. Unless you have an eidetic memory, you will forget a lot of it. Keeping a fencing notebook will allow you to take quick notes on words of wisdom passed on to you, will give you somewhere to scrawl down the website for that new sword guy and something to reflect on down the track. Taking the time to sit down and write out your thoughts on fencing and trying to explain to yourself how and why to do things will give you a stepping stone if you have to take a break at some point, while giving you a starting point to your teaching career if you choose to go that path.

Step 2: Dress the part

When you look at the list field (either one), who draws your eye? The guy in tracksuit pants and modern gear, or the full period outfit? When looking at the heavies, which fighter is more inspiring, the one in badly fitting pickle barrel armor, or a well made kit? Now before you begin with the objections: “Hey Amos, that’s great, but I can’t afford a fancy outfit” or “I suck at sewing” – those are small problems with pre-existing solutions.

1 – Make or Barter

First and foremost, the SCA is about learning new skills. If you’ve never tried to sew an outfit before, there’s no better time than to pop along to a local A&S night and ask for help. In my travels I have yet to meet an SCA group without at least one half talented costumer and I always see a lot of support for helping people with garb – lucky for you, rapier armor is generally just garb with more layers.

If the idea of sewing really just turns you off that much, you also have the option to barter skills. I’m not handy with the arts and crafts outside of cooking, but I’ve successfully cooked a feast in exchange for garb before and I’d do it again. If you lack a skill yet, plenty of people love help setting up and packing down events and an offer to help out at a big event with some grunt work in exchange for some basic clothes usually goes down well.

2 – Beg or Borrow

There is always going to be a financial component to the hobby, thankfully the most expensive part (The sword) is one most will recommend you wait until last to get. Unless you are in the rare situation of having no rapier community in your immediate and surrounding groups, you will find most fighters have a spare sword or two and are usually happy to share if it means they get to stab you.

3 – Keep it classy

Your goal should be to present yourself as best you can on the field, regardless of your actual fighting skill. Find a historical figure or occupation to motivate you and emulate that in your dress as much as possible. Want to be a viking raider on the rapier field? Put together a rapier legal viking outfit, talk to a local swordsmith/woodworker/metalworker/handyperson to make viking sword furniture for your rapier blade. Consider taking a lightweight viking shield out on the field. Fancy yourself a swashbuckler after Sir Francis Drake? Take a look at some of his portraits and work to emulate his outfits. Maybe consider gathering a band of friends together and look at putting on a privateer vs pirate event to further help get into the feel of it. Whatever you choose to do, do it and do it well. Simply rocking up in the minimum and fighting will not make you feel like one of the greats and if you don’t feel like one of the greats you have slim chance to become one yourself.

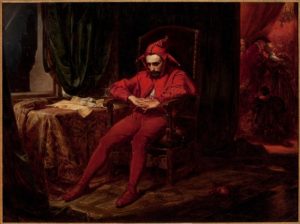

4 – Get a flash hat

From Cyrano to the Three Musketeers to Elizabeth’s Courtiers and practically everyone else in European history, hats were King. In the later period they were symbols of wealth, rank and style, being used to display everything from jewelry to feathers and allowed the wearer to sweep them off in a graceful bow to add to their courtly poise. But hats weren’t just limited to the late period folks, they were a staple throughout history as a way to keep the head warm and dry and were an integral part of the outfit for most anyone. So when you’re building your rapier legal clothes, consider a matching hat for your outfit and persona – you not only add depth to the look you create, but you gain a handy accessory to use when bowing your way into court or when encountering other nobles out and about.

Step 3: Get outside your comfort zone

Spend enough time in any small pond and it’s easy to feel like a big fish. People will come and go but years go by and you’re still there. Once you were brand shiny new but now you’ve been around the block, fought for a few years and can reliably kill a bunch of people 6/10 times. This can be the most dangerous time in your career because you run the risk of thinking that’s it.

1 – Travel is good for the sword and soul

To look at the medieval guild system, an apprentice was expected to stay with a master or teacher and learn from them the basics of the trade or craft. Only once they were deemed competent with the basics and their own work/skill were they promoted to journeymen, allowed to produce for themselves and travel to learn from others – and so it is in fencing.

Learning the basics is just one step in a long journey. It’s easy to feel good fighting your regular training partners because you learn all their habits (good and bad) and learn how to counter them. I get good results on local fencers of a much higher skill level, simply because of the familiarity. But we all know conflict and challenge improve skills – so the question is, do you want to stay a big fish in a small pond, or do you want to learn how to swim in the ocean?

To do so, you’ll need to travel and fight new people. Large events are great for this as they attract fighters from all over and serve as an excellent measuring point to test your skills against people you might see only once or twice a year.

2 – Back to school

Once you’ve been fighting and training for a few years, you may find yourself in a strange situation. You may be asked or expected to help pass those skills on to fresh newcomers. This can seem challenging, but it can be one of the most rewarding experiences of your fencing career. Having to go back to bare basics and realizing your footwork isn’t quite as neat as it should be, having to focus on controlling your shots and parries to demonstrate good skill, having to scale your fighting skill and speed to your opponent – all these are core aspects of teaching and will give you a new appreciation for your teachers. Teaching a newcomer will force you to go over the basics yourself and sharpen your game, giving you a deeper appreciation than you previously had.

3 – Developing a (positive) attitude

The SCA is full of social misfits. This isn’t a criticism, it’s just a statistic. But we come together to become something greater than what we start as. A lot of us can be shy people, some may be young and unfamiliar with social situations. Rapier can help grow you as a person, and more than just learning how to stab people in style. Historically in the SCA, the Queen is the patron of the art of Rapier, and fencers generally fight for her honour. This is paralleled in history looking at Elizabeth’s Courtiers who kept her company, guarded her and served in her court, while showing grace and courtesy. I’m not suggesting you go up to your Queen and jump into the role of her retinue without being asked, but I do suggest you become the kind of person who may be asked to do so at some point in the future.

Introduce yourself to people and be polite. Meet people and make new friends. Show courtesy to all – a kind word here, holding a door here, a smile there – they are all worth more than their weight in gold and contribute vast amounts to our society and the culture of rapier fighters as a whole. If you see a Gentle carrying something heavy that you could lift, ask them if they need help. Little things like this go a long way and all help develop your persona off the field.

Suddenly, instead of being the person who turns up in the bare basics just to fight, you become a friend who turns up in an awesome outfit who has a cheer squad because people want to see their friend do well, and from there things can only go up.

I don’t claim to be an expert on this, I’m still trying to improve my look and attitude and develop myself into something positive for rapier and the Society. I aim to share a blog post in the (near) future about the progress I have made myself. If you have a personal story of progress in rapier you want to share, please get in touch (amos@ironbeard.net) – I’d love to hear from you.